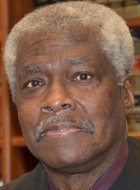

Arlander Keys

Arlander Keys

On the rare occasions he starts to think he’s working too hard, U.S. Magistrate Judge Arlander Keys looks at two items he keeps in his chambers.

One is a jar of cotton, the crop he picked from sunup to sundown for $2 per 100 pounds — work he started when he was 6 years old.

The other is a photograph taken at the 1955 funeral of the Rev. George W. Lee, a minister from Keys’ hometown of Belzoni, Miss. The man was murdered for urging black people to register to vote.

Those two items remind him how hard life can be and how things have changed for the better for him and other black people, Keys said.

“We’ve come so far,” he said. “I’m blessed.”

Those who know Keys say he created his own blessings.

Geraldine Soat Brown, the Northern District of Illinois’ presiding magistrate judge, said Keys has worked steadily without a break during his 19 years on the bench.

Noting that Keys is a former Marine, Brown said he exemplifies the Corps’ motto — semper fidelis, Latin for always faithful.

“It demonstrates exactly the qualities that have made him a good judge, which are steady determination, discipline, intelligence,” she said.

Keys will soon be applying those qualities to new job responsibilities.

He is leaving the bench at the end of this week to join JAMS Inc. where he will work as a mediator and arbitrator.

But first, Keys is going to take some time off with his wife.

“I don’t know how I would handle a vacation,” Keys said. “But, you know, we do what we have to do.”

Keys, 70, was raised by his grandparents, Liddie and Thomas Keys.

While white children were required to go to school, Keys said, black children attended class only when the weather was too bad to chop cotton.

Restaurants refused to serve blacks, restrooms and water fountains were segregated and black people had to sit or stand in the back of buses, Keys said.

He and his grandparents had to bring food with them when they took the train to Chicago to visit his mother, Louise Mason, since blacks were not allowed in the dining car.

“I witnessed the most degrading system of discrimination that one can imagine,” he said.

The atmosphere in Belzoni became tense, Keys said, following the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), declaring “separate but equal” public schools for black and white children to be unconstitutional.

The situation got “really hot” the following year, he said, after Lee’s murder and the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in nearby Money, Miss., less than four months later.

A couple of years after the slayings, Keys’ grandparents, who were devout Seventh-day Adventists, sent Keys and a cousin to a religious boarding school in Huntsville, Ala.

Keys worked eight hours a day at a farm and dairy and attended classes in the afternoon.

After graduating, Keys came to Chicago and went to work as a letter carrier for what was then called the U.S. Post Office Department.

In 1963, he enlisted in the Marine Corps. During his four years in the Marines, he served two 13-month tours of duty in Vietnam.

Keys returned to Chicago in 1967 and rejoined the post office. He worked full time as a carrier during the day while attending DePaul University at night and on weekends.

After earning an undergraduate degree in political science in 2½ years, Keys started law school.

He sped through his studies because he wanted to get as far as possible in school before the 36 months of tuition covered by the GI Bill ended.

Keys entered law school after his stepfather, Ivory Mason, asked a lawyer friend to write a letter of recommendation for his stepson. And Keys did well on the LSAT.

After earning his law degree in 1975, Keys joined the National Labor Relations Board as a trial attorney.

He became regional counsel to the Federal Labor Relations Authority in 1980. The agency handles disputes over matters including collective bargaining agreements and allegations of unfair labor practices involving the federal government and its employees.

In 1986, Keys was appointed an administrative law judge for the Social Security Administration Office of Hearings and Appeals. He served as chief ALJ from 1988 to 1994.

In 1994, he was selected by the federal district court judges in Chicago to serve as a magistrate judge. He began an eight-year term in that post in early 1995. He was appointed to a second term in 2003.

Keys served as the presiding magistrate judge from 1998 to 2004. He retired on Oct. 31, 2009, but was recalled to the bench the following day.

Like district and appellate judges who have taken senior status, Keys is donating his services.

He has not gotten a paycheck for the past 4½ years. Instead, he has received only his pension, which he would have received even if he had remained retired.

Keys said he was inspired to seek a seat on the bench by the federal judges in the South — all of them white; there were no black judges at the time — who helped end segregation.

Much of his work involves trying to help litigants resolve their disputes without going to trial or submitting motions for summary judgment.

“I enjoy the fact that a judge makes a difference in people’s lives — hopefully, a positive difference,” Keys said.

He acknowledged that “somebody’s going to win, and somebody’s going to lose” if the parties do not settle a case.

But there is an advantage to taking a dispute through the legal process, Keys said.

“Everybody should have equal chance under the law to present their cases to an individual who has no stake in the outcome,” he said. “And, hopefully, regardless of how it turns out, at least the parties will feel that they got a fair shake.”

U.S. Magistrate Judge Young B. Kim said he always got a fair shake when he appeared before Keys as a federal prosecutor.

“He’s the kind of judge who you knew going in would listen to what you had to say,” Kim said.

When he was appointed a magistrate judge in 2010, he said, he took “less than a second” to select Keys as his judicial mentor.

“He’s answered all my calls and been very patient with me, and he’s been willing to share his knowledge,” Kim said. “We are going to miss him.”