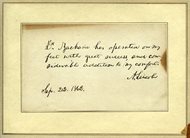

In an 1862 letter, President Abraham Lincoln recommends his podiatrist Issachar Zacharie’s services. A year later, Lincoln reportedly said, “My chiropodist is a Jew, and he has so many times ‘put me on my feet’ that I would have no objection to giving his countrymen ‘a leg up.’”

In an 1862 letter, President Abraham Lincoln recommends his podiatrist Issachar Zacharie’s services. A year later, Lincoln reportedly said, “My chiropodist is a Jew, and he has so many times ‘put me on my feet’ that I would have no objection to giving his countrymen ‘a leg up.’”

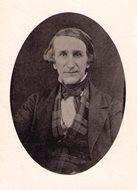

Abraham Jonas, the first Jewish resident of Quincy, a lawyer and a state legislator at the same time as Abraham Lincoln. Jonas is credited with organizing the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates. — Photo provided by the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

Abraham Jonas, the first Jewish resident of Quincy, a lawyer and a state legislator at the same time as Abraham Lincoln. Jonas is credited with organizing the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates. — Photo provided by the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

SPRINGFIELD — Abraham Lincoln may not have ascended to the White House without another lawyer named Abraham.

Abraham Jonas, a state legislator and the first Jewish settler in Quincy, helped organize the debates between Lincoln and Stephen Douglas that vaulted Lincoln to prominence, promoted his run for president and warned Lincoln of death threats that prompted him to travel to Washington, D.C., in secret after his election to the presidency.

Their friendship highlights Lincoln’s warmth toward Jewish-Americans at a time when anti-Semitism was rampant, and it’s a primary focus of a new exhibit slated to open next week at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

“With Firmness in the Right: Lincoln and the Jews” is based on a similar exhibit from New York. It will open Monday and run through Nov. 15.

It features letters the 16th president swapped with Jonas; a Hebrew-inscribed American flag painting given to Lincoln before he took office by another Jewish friend, Abraham Kohn, and a tracing of Lincoln’s feet done by a German bootmaker after he had been treated by a Jewish podiatrist, Issachar Zacharie.

Zacharie is described in the exhibit as “eccentric.” But he served as a liaison for the president to Jewish communities, campaigned for his re-election, freed Jewish prisoners taken by the Confederacy and claimed to have spied for the Union by tracking troop movements and collecting intelligence.

“My chiropodist is a Jew, and he has so many times ‘put me on my feet’ that I would have no objection to giving his countrymen ‘a leg up.’” Abraham Lincoln reportedly said to a friend in 1863.

Before 1862, Army chaplains had to be ordained and “of a Christian denomination.” Lincoln successfully petitioned Congress to change the law to allow Jewish chaplains, and also appointed the first Jewish quartermaster, a position in charge of military housing and supplies.

The exhibit also shows Ulysses S. Grant’s infamous “General Orders No. 11,” a December 1862 command in which he blamed Jewish people for smuggling cotton from Union-occupied plantations and expelled them from the area under his army’s control, which stretched from Mississippi to southern Illinois.

Lincoln revoked the order almost immediately, and Grant would soon come to regret it.

“Lincoln advised Grant, and Grant adored Lincoln, and then the next step is he meets a lot of Jews himself, which he had never ever been exposed to,” said Eileen Mackevich, the museum’s executive director. “And so once he sees people that are like himself: curious, interested, artistic, creative — he changes.”

The title of the exhibit is taken from a line in Lincoln’s Second Inaugural address — which some consider his most profound wish ever: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

The speech is infused with religious overtures and allusions to the Hebrew Bible, and notes that all sides of the Civil War appealed to the same God.

It’s this idea — Lincoln’s inaugural gestures toward a commonality and acceptance — that shaped the exhibit, said Urshula Barbour, co-principal of the New York City-based design studio Pure & Applied who worked on both this exhibit and the one in New York.

“This exhibit has that same content but it really weaves it together and explains it more in the context of the Second Inaugural and the threads of the Second Inaugural,” Barbour said. “And how while many people know about the history of Lincoln and emancipation and that sort of thing, they aren’t as familiar with the fact that a thread in that Second Inaugural was his openness to Jews and Jewish culture.”

Although he had nearly cemented his presidential legacy, Lincoln never forgot Jonas back in Illinois. All but one of Jonas’ sons fought for the South during the war, but Lincoln gave one of them a three-week parole from a Union war prison so he could see his father before he died in June 1864.

Additionally, after his death, Lincoln appointed Jonas’ widow Louisa to fill his role as postmaster.

To this day, Jonas — Lincoln’s legal contemporary and likely the first Jewish-American he got to know well — is the only known person whom he described as “one of my most valued friends."