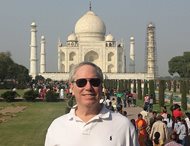

Fischel & Kahn Ltd. managing partner David W. Inlander stands before the Taj Mahal while in India in November as part of a trip through the American Jewish Committee. He serves as chair of the AJC’s Interreligious Affairs Commission, which works to foster positive relations between the Jewish community and members of other religions across the globe. — Photo provided by David W. Inlander

Fischel & Kahn Ltd. managing partner David W. Inlander stands before the Taj Mahal while in India in November as part of a trip through the American Jewish Committee. He serves as chair of the AJC’s Interreligious Affairs Commission, which works to foster positive relations between the Jewish community and members of other religions across the globe. — Photo provided by David W. Inlander

If you thought working in divorce court was contentious, try improving relations between millenia-old religions.

Promoting respect and understanding between faiths is what David W. Inlander does in his spare time.

Inlander, the managing partner at Fischel & Kahn Ltd., focuses his professional life on complex family law and alternative dispute resolution. In his personal life, he serves as chair of the American Jewish Committee’s Interreligious Affairs Commission.

The 110-year-old AJC is a Jewish advocacy organization that holds diplomatic meetings, promotes domestic policies and legislation and builds coalitions with other religious groups.

Inlander helps lead trips across the world to get to know leaders of other religions.

“If people who have been at odds with one another over faith for hundreds or thousands of years can figure out ways to come up with solutions to live together peacefully, to understand each other and to mutually respect one another, then certainly husbands and wives who had hopefully many years of happiness before they became unhappy with one another ought to be able to figure out ways to reach amicable resolution of their disputes,” he said.

Inlander has met with Pope Francis three times, including a private audience the pontiff held with the AJC in 2015 honoring the 50th anniversary of Nostra Aetate, a document that opened relations between the Catholic Church and non-Christian religions in 1965.

The declaration said Jewish people cannot be collectively blamed for Jesus’ death and decried anti-Semitism, repudiating a belief Christian mobs used since the early days of the church to incite violence against Jews.

As a gift, Inlander presented Pope Francis a print of a painting that hangs at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Pope Francis had been on the record saying that the canvas “White Crucifixion” by Marc Chagall — one of the 20th century’s most famous Jewish artists — was his favorite piece of art, so Inlander had a copy and binding made and presented it during the meeting.

Inlander said Francis put a hand to his heart and said in English, “That’s ‘White Crucifixion.’”

The painting depicts the crucifixion of Jesus as a symbol of Jewish suffering. Jesus wears a tallit — a Jewish prayer shawl — in place of a loincloth and is surrounded by scenes including a man with a burning a Jewish village and other historical images of violence against Jewish people.

“You ever have the experience of going to a friend’s house and bringing a bottle of wine and the hostess says, ‘Oh, this is just perfect for what I’m making?’” Inlander asked. “That was like the perfect present.”

In November, Inlander co-led a trip of 18 AJC leaders to India after two swamis invited them as guests at religious ceremonies.

At Dev Deepawali, the annual festival of lights of the gods in the city of Varanasi, AJC members took a five-mile boat ride up the Ganges River as hundreds of thousands of people celebrated along the banks of the holy river. They arrived at an interfaith celebration in an outdoor amphitheater with about 50,000 people attending, in Inlander’s estimate.

There were Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Sikh, Jain, and Christian guests of honor at the Hindu event to celebrate the mutual understanding of religion. The head swami had the crowd cheer for each religion, introducing each member and placing a saffron scarf around them.

Inlander said he felt a tremendous pride, both of his own Jewish identity and his interreligious work. He said celebrating religious pluralism in front of a crowd of 50,000 people cheering, chanting, singing and waving flags was astounding.

“We live in a world where sometimes religious differences are not used positively, to say the least,” he said. “Here was an example of using religious pluralism for such a positive impact. And the crowd responded to that so beautifully.”

It was an explosion of sights and sound, Inlander said, with fireworks going off nonstop, music blaring and buildings and steps decorated leading down to the river.

The next morning, as the AJC delegation took a sunrise boat ride on the Ganges, Inlander watched thousands of people silently come to the river to wash away their sins. Inlander said the contrast between the two experiences was incredibly spiritual.

The following day, the AJC delegation traveled to Rishikesh. The city, known as the yoga capital of the world, sits at the base of the Himalayas and became famous in 1968 when the Beatles visited the now-closed ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

The Jewish group was part of another international, interfaith ceremony during a Hindu religious ritual that asked Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, Sikh, Jain, Christian and Jewish communities to work together to protect the world’s environment.

Members of each faith poured water over a globe about the size of the one Inlander remembers being in his third-grade classroom. The ritual represented their common commitment to efforts to save the environment.

The AJC members then joined other religious leaders as featured guests as the local school with 1,100 kids debuted the building’s sewage system. These were the first toilets those kids had ever had, Inlander said, which was an almost incomprehensible thought for him.

“Everything in India, including this, gives you such an entirely different perspective on a way of life and of the importance of things that we take for granted here,” he said.

Inlander got involved with the AJC in 1986. He was sitting through a 45-minute debate in his condominium board meeting about whether to turn the building’s heat on one week earlier. Inlander said he was “banging [his] head against the table” when the woman next to him said he was wasting his time and introduced him to the AJC instead.

From 2003 to 2005, he was president of the Chicago’s regional AJC office.

He’s been chair of the AJC Interreligious Affairs Commission for the past four years and was vice-chair for three years before that.

Inlander said the AJC is applying the kinds of lessons gained from the trip to India to the interreligious group it launched in November with the Islamic Society of North America.

The Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council is bringing together business, political and religious leaders in Jewish- and Muslim-American communities to advocate against anti-semitism and xenophobia.

He said that with both interreligious conflicts and contentious divorce, he’s found if you get people in a room to focus on each other, you can accomplish a great deal.

Carlton R. Marcyan, a partner at Schiller DuCanto & Fleck LLP, called Inlander an optimist. He met Inlander as opposing counsel on a tedious case with difficult clients about seven years ago. He said Inlander is a pleasure to work with and keeps everyone cool and collected to find a solution.

“That’s his personality,” Marcyan said. “He’s wanting to find the common denominator, whether it be in cases or on a more global perspective with the religious issues.”

Inlander said his AJC work, and his legal practice, are guided by tikkun olam — the central Jewish concept that translates from Hebrew to “repair the world.” It’s used today to signify an emphasis on justice and social responsibility.

Inlander said he remembers how the Pope looked him in the eyes while he presented “White Crucifixion” as if he were the only person in the world that he cared about in that moment. To have someone who represents nearly 1.3 billion Catholics look, listen and understand the significance of the art was incredibly powerful, he said.

And he said he’s taken that home to his practice.

“If I look them in the eye and I listen and I try and understand their point of view, I have found that it is very effective in terms of my practice and my ability to try and come up with creative solutions to solve their problems,” Inlander said. “I learned something from that.”